This review of Airborn by Kenneth Oppel and A Hatful of Sky by Terry Pratchett first appeared in the New York Review of Science Fiction 197, January 2005. It was, I was surprised to discover, the only review I ever wrote of anything by Pratchett, though there is an interview I did somewhere around the time of Pyramids which I may try to dig out at some point.

We learn from books; which is probably one of the principal reasons we read in the first place, though we may not always acknowledge that fact. What we learn will vary as we grow older, of course, so a favourite book is likely to take on a very different coloration when we revisit it in later life. It is the nature of this learning, I think, that is the major difference in books written for children and those aimed at an adult audience. We may say that books for children use simpler language, though the two books under review use language as rich as many adult novels; we may say they eschew darker issues of sex and violence, but so do many adult novels, and these two at least acknowledge varying relationships between the sexes; we may say they are essentially simpler in structure or concept or some such, but these are both complex works. No, I think the primary difference is that the intended audience for these books have more to learn and are happier to take all they can discover from the books they read. We grown-ups like to pretend we are too sophisticated for all that, so our lessons have to be disguised; but the readers of these novels will happily devour broad introductions to questions of what is right and wrong, what we should and should not do in various circumstances, how to behave.

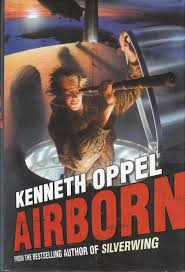

There are times, of course, when as an adult we would find either of these books too didactic, too blatant in its teachings. But in the main the lessons are placed within a sugar pill of action and adventure, and there is story enough here to keep most of us reading happily. Of the two, Kenneth Oppel’s Airborn is the more old-fashioned, a straightforward rite of passage tale laced with derring-do that would not have been out of place among the children’s novels of my own youth. All that is different is that the heroine is allowed to be bold, intelligent and effective in a way that would have been confined to the male lead in the tales I remember. Other than that it is a yarn of breakneck pace and ever-new perils indistinguishable from those which have been holding readers of all ages agog for a century or more. The ingredients are all there: pirates, shipwreck, exotic creatures; it could have been written by Robert Louis Stevenson. That the stately galleon whose cabin boy must save the day against each new threat happens to be an airship rather than a three-master is the only thing that really separates it from a host of successors to Treasure Island.

There are times, of course, when as an adult we would find either of these books too didactic, too blatant in its teachings. But in the main the lessons are placed within a sugar pill of action and adventure, and there is story enough here to keep most of us reading happily. Of the two, Kenneth Oppel’s Airborn is the more old-fashioned, a straightforward rite of passage tale laced with derring-do that would not have been out of place among the children’s novels of my own youth. All that is different is that the heroine is allowed to be bold, intelligent and effective in a way that would have been confined to the male lead in the tales I remember. Other than that it is a yarn of breakneck pace and ever-new perils indistinguishable from those which have been holding readers of all ages agog for a century or more. The ingredients are all there: pirates, shipwreck, exotic creatures; it could have been written by Robert Louis Stevenson. That the stately galleon whose cabin boy must save the day against each new threat happens to be an airship rather than a three-master is the only thing that really separates it from a host of successors to Treasure Island.

We begin with Matt Cruse dangling on a line from the airship Aurora hundreds of feet above the Pacific as he attempts to rescue an old man lying injured in the basket of a hot-air balloon miles from nowhere. The old man dies, leaving a peculiar tale of unknown flying creatures. A year later, and one of the wealthy passengers aboard the Aurora is Kate, the spirited young granddaughter of the dead man, determined to prove his claims about the strange creatures in the face of scepticism from the scientific establishment. Cabin boy and rich girl form an unlikely alliance as the Aurora is first raided by ruthless pirates, then shipwrecked on an uncharted island which just happens to be the nesting ground of the flying mammals and also the secret base of the pirates. It is Matt who finds the supply of natural ‘hydrium’ which allows them to re-inflate the airship; and it is Matt and Kate who, alone, can save the day when the pirates take over the Aurora once more.

It’s a swashbuckler with a stylish 1930s feel to it (both in the setting and in the tone of the narrative) and rather obvious messages about loyalty, bravery, learning to respect one’s rivals and other old-fashioned virtues. Sometimes the messages feel too blatant, and one does occasionally wonder whether its intended audience really will get on with the style well enough to absorb the lessons? It is the sort of novel for young readers that is likely to appeal most to an older audience, readers for whom it recaptures youth, readers who feel they are allowed to enjoy a simple adventure story because it’s ‘really’ for kids.

Terry Pratchett, on the other hand, has worked out that one of the secrets of writing for children is to pretend you are writing for adults. Or maybe that is just a side effect of the way he has arrived at this latest Discworld escapade. He has been spattering books for children in among his adult work throughout his career, but it is only the last few which have been set on the Discworld even though it has always been popular with young readers. It is no coincidence, I suspect, that these novels, starting with The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, have been the most successful of his books for children. The latest, a direct sequel to The Wee Free Men, is virtually indistinguishable from any of his other Discworld novels; fewer footnotes, maybe, but otherwise much the same cast of characters, the by-now very familiar terms of reference, and the same sense of humour. And the Wee Free Men themselves, an amalgam of every legend ever told about belligerent Scots rugby fans, are the sort of funny hard nuts with a soft centre that have always populated this riot of half-baked mythology (think of Death, for example, the City Guard, or, more pertinently here, the witches). As the character of Death indicates, Pratchett has always somehow managed to tackle big issues; and though the skeletal figure doesn’t appear, in disguised form this is a children’s novel about death.

Terry Pratchett, on the other hand, has worked out that one of the secrets of writing for children is to pretend you are writing for adults. Or maybe that is just a side effect of the way he has arrived at this latest Discworld escapade. He has been spattering books for children in among his adult work throughout his career, but it is only the last few which have been set on the Discworld even though it has always been popular with young readers. It is no coincidence, I suspect, that these novels, starting with The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents, have been the most successful of his books for children. The latest, a direct sequel to The Wee Free Men, is virtually indistinguishable from any of his other Discworld novels; fewer footnotes, maybe, but otherwise much the same cast of characters, the by-now very familiar terms of reference, and the same sense of humour. And the Wee Free Men themselves, an amalgam of every legend ever told about belligerent Scots rugby fans, are the sort of funny hard nuts with a soft centre that have always populated this riot of half-baked mythology (think of Death, for example, the City Guard, or, more pertinently here, the witches). As the character of Death indicates, Pratchett has always somehow managed to tackle big issues; and though the skeletal figure doesn’t appear, in disguised form this is a children’s novel about death.

Young Tiffany Aching (and the presence of a child protagonist is really the only thing that marks this novel out as a book for children) begins her apprenticeship as a witch, only to discover that for the most part it doesn’t involve magic at all, but rather a kind of social service wrapped in smoke and mirrors. There aren’t that many novelists who would make the care of old people the central concern in a comic novel for children. But of course Tiffany, as we discovered in her last appearance, has a natural if unschooled talent for real magic, and the spells she unthinkingly casts bring her to the attention of an immense bodiless creature known as the Hiver, a remnant from the creation of the universe that cannot be killed and cannot be defeated. What the Hiver really craves, of course, is a sort of death. The witch to whom Tiffany is apprenticed has a poster for an old circus which advertises ‘See the Egress’, the circus master used it as a temptation to keep people moving through the exhibits. It is Tiffany’s job to show the Hiver the egress, which she does in a great set-piece confrontation at the Witch Trials (it is a typical Pratchett pun to make this not a court hearing but a sort of sheep dog trial for witches). In this she is aided by Granny Weatherwax, who has now become such a familiar figure in the Discworld that Pratchett can give her little more than a walk-on part and still have her dominate the novel.

Though A Hat Full of Sky is more subtle (and funnier) than Airborn, it’s lessons – on death, self-control, and the need to help others – are every bit as straightforward, not to say blatant. I suspect that the sugar coating is more effective in Pratchett’s novel, which will help the pill go down more easily with its intended audience. But I suspect that many of us who have forgotten that one of the reasons we read is to learn the moral lessons of the world would also profit from reading either of these books.