Tags

Anthony Powell, Barbara Skelton, Cyril Connolly, D.J. Taylor, Edmund Wilson, Evelyn Waugh, Feliks Topolski, George Orwell, George Weidenfeld, Ian Lubbock, Janetta Woolley, Joan Leigh Fermor, Lys Connolly, Michael Shelden, Patrick Leigh Fermor, Peter Quennell, Sonia Brownell, Stephen Spender

Back in the 1980s, Michael Shelden wrote Friends of Promise, an account of Cyril Connolly and the circle around him at Horizon, the literary magazine he edited throughout the 1940s. It remains the definitive work on this key aspect of literary London during wartime. That is the book, I think, that D.J. Taylor wanted to write. He had, after all, already written a biography of George Orwell, probably the most significant writer to have been published in Horizon (and, curiously, Shelden would follow up Friends of Promise with a biography of Orwell). Taylor had also written a book on the Bright Young Things of London society during the gilded age of the 1920s, and also The Prose Factory, a survey of literary life in England since 1918. Within such a spectrum of interest, Horizon and Connolly is not just a natural fit, it almost feels like the inevitable next step.

But Shelden had already taken that step, and despite the fact that letters and diaries and other resources have emerged since Shelden’s book was published, it is unlikely that Taylor would really have been in a position to write a startlingly new and different take on the same subject. So he let his gaze wander from the centre to the periphery, in particular to the young women who circled around Connolly, as lovers (or occasionally wives), secretaries, helpmeets, confidants. There were four of them in particular: Lys, Janetta, Sonia and Barbara. Collectively, Taylor calls them the “Lost Girls”, taking the term from Peter Quennell’s autobiography, The Wanton Chase. Taylor doesn’t wholly accept Quennell’s term, but he doesn’t exactly question it either. My own sense, on the other hand, is that they were neither lost nor girls. They were beautiful, ambitious, sexually active young women who found themselves in a particular wartime bohemia, and they took advantage of their circumstances that would have been unquestioned, even unremarked, if they had been men. The women who came before them in the 1920s were the same, as were the women who came after them in the 1960s, but because this was the 1940s they were somehow regarded as courtesans. Men who behaved the same would have been hailed as adventurers. Taylor doesn’t lay out the contrast so starkly, I’m not even sure he is fully aware of it, but it is there buried in the assumptions and subtexts of the book.

It is notable, for instance, that the first view of any of these women in Lost Girls: Love, War and Literature 1939-1951 comes from the male gaze. After Quennell’s description of the lost girls in general, there are four single-sentence quotations, one for each of the women: Edmund Wilson on Barbara, Stephen Spender on Sonia, Evelyn Waugh on Lys, and George Weidenfeld on Janetta. The women are perennial adjuncts to the men, to be seen from outside. The real interest is in the men who are doing things in Horizon, these women are just there to provide a different perspective on the main action.

Lys, Janetta, Sonia and Barbara: the men in this book are Connolly, Quennell, Orwell, Waugh, Topolski, and so on, but the women are always addressed by their first names. In a long preamble, Taylor explains this as being because their surnames changed so often. Lys, for example, began life as Lys Dunlap; she married Ian Lubbock but soon thereafter left him to become Cyril Connolly’s mistress, changing her name to Connolly by deed poll when he wouldn’t marry her; after she left Connolly at the end of the decade she eventually married again and became Lys Koch. But she was Lys Lubbock or, by her own choice, Lys Connolly, for the entire period covered by this book. Sonia Brownell was known by that name throughout the 1940s until, right at the end of the decade, she became Sonia Orwell; similarly, Barbara Skelton had that name throughout the decade until, in the closing pages of the book as it were, Lys left Connolly and Barbara became, for a while, Barbara Connolly. Significantly, when she began publishing books in the 1950s she published under the name Barbara Skelton. There must, I think, have been more subtle, less sexually pointed ways, of identifying the various characters throughout the book.

Without exception, by the way, the men in this book are total shits, and the shittiest of them all is Cyril Connolly. At the end of the 1930s he was married to Jean but had left his wife to live with Diana, whom he then left to live with Lys. Lys remained his mistress, housekeeper, secretary, hostess of his innumerable parties, and general dogsbody for nearly ten years, but he would not marry her and spent an inordinate amount of time belittling her in conversation. Yet when she did leave him he spent years stalking her, bombarding her with letters, and insisting that they should get back together, all while having now married Barbara. This, by the way, was serial behaviour: when his marriage to Barbara ended, George Weidenfeld was cited in the divorce; when that marriage ended, Cyril Connolly was cited in the divorce. But it wasn’t just his treatment of women that was execrable. At the centre of this whole menage was the magazine, Horizon, which he had launched in December 1939. Part of the thinking behind this launch seems to have been that as editor he would be in a reserved occupation and thus not liable for any form of war work. The magazine was major literary and artistic centrepiece in mid-century Britain, but Connolly was a rather lazy editor who left much of the work to the women who worked there. Sonia Brownell in particular seems to have been the de facto if unacknowledged editor of the magazine throughout the last years of its life while Connolly used his expenses to fund foreign travel, a hectic social life, and fine food and wine, while occasionally remembering to write back to base and ask, casually, how the magazine was going.

Actually, for a book ostensibly about literary London in wartime, we learn very little about Horizon itself. Only a bare handful of contributors are even mentioned, and there is no analysis of what it published or how it shaped the literary landscape for years to come. George Orwell appears because he went on to marry Sonia; Joan Rayner, whose photographs were published in Horizon, is mentioned because she was a sexually active member of that milieu who Connolly fancied before she went on to marry Patrick Leigh Fermor. Yet this neglect of Horizon as a literary artefact jars with the fact that Taylor is a good literary historian. One of the best things about this book, something that does make it well worth reading, is the adept way he uses novels and memoirs of the period to paint a vivid picture of how things were at the time. And there is a fine late section of the book in which Taylor traces the afterlife of the four girls in postwar novels by writers who knew them at the time. Barbara, for instance, is a recurring character in Anthony Powell’s Dance to the Music of Time sequence.

All told, therefore, it is an interesting and at times revealing book hampered by the way it approaches the four women who are supposedly its central subject matter.

The Patrick Leigh Fermor industry has been busier since his death than he ever was in his lifetime. This year alone we have had a wonderful exhibition at the British Museum devoted to Leigh Fermor, Niko Ghika and John Craxton; which was in turn accompanied by an even more wonderful book, which to my mind is a model of what a book associated with an exhibition should be like. And now Ian Collins and Olivia Stewart have produced The Photographs of Joan Leigh Fermor: Artist and Lover. (Personally, I could have done without the somewhat saccharine quality of that subtitle; but then I could have done without much of the account of her life that occupies rather too much of this book, particularly since so much of it is devoted to telling us, repeatedly, how devoted she was to Paddy, and by extension how wonderful Paddy was.)

The Patrick Leigh Fermor industry has been busier since his death than he ever was in his lifetime. This year alone we have had a wonderful exhibition at the British Museum devoted to Leigh Fermor, Niko Ghika and John Craxton; which was in turn accompanied by an even more wonderful book, which to my mind is a model of what a book associated with an exhibition should be like. And now Ian Collins and Olivia Stewart have produced The Photographs of Joan Leigh Fermor: Artist and Lover. (Personally, I could have done without the somewhat saccharine quality of that subtitle; but then I could have done without much of the account of her life that occupies rather too much of this book, particularly since so much of it is devoted to telling us, repeatedly, how devoted she was to Paddy, and by extension how wonderful Paddy was.) Madrid, and finally in 1944 to Cairo, where she met Paddy. (It somehow confirms things I’d begun to suspect from my other reading about Leigh Fermor to see him described here not just as charming, but as “indecisive, impractical and clumsy.”) They met again, after the war, in Greece, and began the romance that, in all I’ve read, seems to subsume everything else about her.

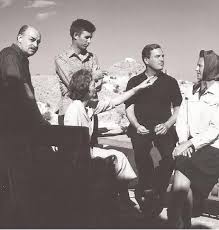

Madrid, and finally in 1944 to Cairo, where she met Paddy. (It somehow confirms things I’d begun to suspect from my other reading about Leigh Fermor to see him described here not just as charming, but as “indecisive, impractical and clumsy.”) They met again, after the war, in Greece, and began the romance that, in all I’ve read, seems to subsume everything else about her. She used, practically throughout her life, a Rolleiflex taking a square 6×6 negative. To show them at their best, the book is (almost) square, with the photographs placed in the middle of a grey page. It is a presentation that I find benefits the photographs while at the same time being frustrating to the viewer. I’ll come to the frustrations in a moment, but first let me just extol the pictures themselves. The early ones are haunting evocations of war-damaged London: an arched gateway set within fragments of wall at Haberdasher’s Hall, with nothing else standing, and in the foreground snow piling on the rubble before the gate; a barrage balloon floating almost directly above the tower of Hawksmoor’s St Anne’s seen from the grime of Limehouse Cut. There are too few of these, then suddenly we are in Greece and the character of the photographs has changed dramatically. Some are almost abstract: square blocks of an old village standing above a winding pattern of terraces like one of Ghika’s landscapes; a small family of goats plodding wearily up a zigzag stairway clinging precariously to a cliffside. Some are touristy: the Lion Gate at Mycenae, the ruins at Delphi, archetypal orthodox churches almost disappearing into rugged landscapes. Some really are family snaps: Paddy, of course, dancing among ruins or gazing moodily into the distance; and friends like Xan Fielding and Lawrence Durrell and John Craxton. There’s a wonderful series of

She used, practically throughout her life, a Rolleiflex taking a square 6×6 negative. To show them at their best, the book is (almost) square, with the photographs placed in the middle of a grey page. It is a presentation that I find benefits the photographs while at the same time being frustrating to the viewer. I’ll come to the frustrations in a moment, but first let me just extol the pictures themselves. The early ones are haunting evocations of war-damaged London: an arched gateway set within fragments of wall at Haberdasher’s Hall, with nothing else standing, and in the foreground snow piling on the rubble before the gate; a barrage balloon floating almost directly above the tower of Hawksmoor’s St Anne’s seen from the grime of Limehouse Cut. There are too few of these, then suddenly we are in Greece and the character of the photographs has changed dramatically. Some are almost abstract: square blocks of an old village standing above a winding pattern of terraces like one of Ghika’s landscapes; a small family of goats plodding wearily up a zigzag stairway clinging precariously to a cliffside. Some are touristy: the Lion Gate at Mycenae, the ruins at Delphi, archetypal orthodox churches almost disappearing into rugged landscapes. Some really are family snaps: Paddy, of course, dancing among ruins or gazing moodily into the distance; and friends like Xan Fielding and Lawrence Durrell and John Craxton. There’s a wonderful series of  photographs of Margot Fonteyn and Frederick Ashton performing dance exercises on the deck of a caique, using the ship’s rail as a bar; and there is a beautiful picture of Fonteyn sunbathing nude. But it is the photographs of rural life in Greece that are so wonderful: a muezzin calling out from a ramshackle wooden platform; craggy-faced shepherds in baggy pantaloons grasping crooks taller than they are; clusters of women in traditional costume; an old soldier with a long white beard and his rifle; young men clustered round a ricketty table in a crumbling kafeneion; the ribs of a boat that is being built but that looks like the skeleton of some long-dead sea monster. These are amazing glimpses of something alien and yet extraordinarily human.

photographs of Margot Fonteyn and Frederick Ashton performing dance exercises on the deck of a caique, using the ship’s rail as a bar; and there is a beautiful picture of Fonteyn sunbathing nude. But it is the photographs of rural life in Greece that are so wonderful: a muezzin calling out from a ramshackle wooden platform; craggy-faced shepherds in baggy pantaloons grasping crooks taller than they are; clusters of women in traditional costume; an old soldier with a long white beard and his rifle; young men clustered round a ricketty table in a crumbling kafeneion; the ribs of a boat that is being built but that looks like the skeleton of some long-dead sea monster. These are amazing glimpses of something alien and yet extraordinarily human.

Ghika’s paintings could be, I think, somewhat disturbing. They were crowded with labyrinthine twists and turns in which the more you looked at them the more you seemed to be lost. But they were overgrown with a profusion of plants and leaves and flowers, a riot of colours, as if they were something out of a Jeff VanderMeer novel. And there, among Ghika’s friends, among the regular visitors to his home on Hydra, was George Katsimbalis, who was Henry Miller’s Colossus of Marousi, which brings us back round to tie in another set of connections.

Ghika’s paintings could be, I think, somewhat disturbing. They were crowded with labyrinthine twists and turns in which the more you looked at them the more you seemed to be lost. But they were overgrown with a profusion of plants and leaves and flowers, a riot of colours, as if they were something out of a Jeff VanderMeer novel. And there, among Ghika’s friends, among the regular visitors to his home on Hydra, was George Katsimbalis, who was Henry Miller’s Colossus of Marousi, which brings us back round to tie in another set of connections. But the work we both fell in love with was by John Craxton. Bold lines, often very few colours, and an incredible vigorous sense of life, especially in the numerous paintings of groups of men around cafe tables or performing Greek dances. I’d seen his work before, since he provided the cover illustrations for all of Leigh Fermor’s books from Mani onwards, but I hadn’t realised this until we got to the exhibition. There is something pivotal in his work, we kept catching echoes of Paul Nash in one direction, Picasso in another, and was there something Ruralist or even possibly Preraphaelite in some individual pictures? Certainly I need to see more of his work.

But the work we both fell in love with was by John Craxton. Bold lines, often very few colours, and an incredible vigorous sense of life, especially in the numerous paintings of groups of men around cafe tables or performing Greek dances. I’d seen his work before, since he provided the cover illustrations for all of Leigh Fermor’s books from Mani onwards, but I hadn’t realised this until we got to the exhibition. There is something pivotal in his work, we kept catching echoes of Paul Nash in one direction, Picasso in another, and was there something Ruralist or even possibly Preraphaelite in some individual pictures? Certainly I need to see more of his work.